How a simple tale shaped a community

By Emma Smith and Evan Bower

For the people of St. Stephen, New Brunswick, the chocolate bar is and always has been theirs. It all started around 1910. Arthur Ganong, the sixth child in a family of seven, would stuff his pockets full of chocolate before heading out to cast a line into the calm St. Croix River.

Since Arthur’s father, James, co-founded Canada’s first candy company, his snack was never in short supply. He even made his own recipe while experimenting with the family’s jersey cow, adding milk, before the chocolate hardened, to the creamy cocoa liqueur.

He would wrap the chocolate to protect it from the hot sun. It was a lesson he learned quickly, after what was meant for his mouth ended up in the linings of his pockets.

So goes the story of the first chocolate bar, one Arthur’s community still remembers a century later. But it is one that conflicts with other stories held by other communities, just as convinced that theirs is the truth.

The problem is that the chocolate bar was being invented at the same time by other people in other countries. It seems several people worldwide had discovered, independently, that same simple pleasure.

But for St. Stephen, it’s no longer just the story of a candy bar, but a symbol of innovation and perseverance. A statement that although business and power might shift in the nation surrounding them, their community won’t.

Part One- The Journey to Chocolate Town

In 1871, St. Stephen was the Maritime’s connection to the world of business. It was an ideal location for James and Gilbert Ganong, two brothers looking to set up shop in the bustling town. As a border town on the east bank of a river, it was a hub for trade. Ships came and went, heavy with the weight of foreign goods. Men hung off of street cars that howled through the store-lined Main Street. The town felt bigger than it was.

This was until five years later, when an eighty building fire brought St. Stephen’s thriving business district to the ground. This sent many entrepreneurs packing. Ganong Brothers Limited stayed behind, and knowingly or not, became a beacon of hope for St. Stephen’s new era.

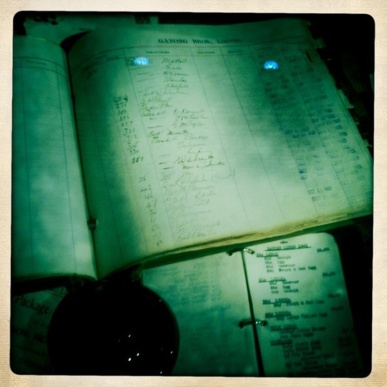

Margaret McCallum, a professor of law at the University of New Brunswick, wrote her doctoral thesis on the Ganong family business. She spent two years flipping through the dusty, hand-written financial statements that make up the Ganong’s history. The kind of casual, vague records you could only find in a family business.

“They had a vault in the basement that no one had been in for years- except rodents,” says McCallum. “And there were stacks and stacks of books there. So every week I’d be hauling something new up.”

She chose to study the Ganong’s because she wanted to study a business that had a history of high female employment.

“It was quite interesting talking to them,” says McCallum of former factory workers. “What they remember is the good times. They talked quite movingly about the good times in the factory. Maybe all the times were good, because they wanted to remember them that way, maybe they didn’t want to say anything that might be perceived as being critical of the Ganongs.”

The only criticism McCallum ever got from a former Ganong employee was from a woman who said, “Well, we didn’t have company picnics the way they did down in Blacks Harbour.”

Most of the company’s employees in the early days were women. They were brought in from surrounding areas like Milltown, and as far away as Europe, to spend hot summer days inside the company’s factory, the old brick building in downtown St. Stephen that is now the Chocolate Museum.

The women would show up around May with their suitcases bursting at the seams, and they’d move in to a bright yellow building on the corner of Main Street.

It was the women who delicately and artfully hand dipped the thousands of little chocolate squares. It was the women who in one graceful motion dunked the truffle or maple cream into a pool of dark, smooth chocolate, and with a twist of the hand finished it off with a swirl.

It became Ganong’s trademark.

Today, the rooms that were once full of busy hands covered in chocolate have largely been replaced with machines. The tradition of hand dipping chocolate is an expensive and time-consuming one. It takes three years to master the art.

But not all the hand dippers have disappeared from St. Stephen. If you happen to tour the town’s Chocolate Museum you’ll come across a handful of women who still practice the craft.

St. Stephen’s Mayor, Jed Purcell says, “There’s pride in the community because chocolate was handed down. It was a science and an art.”

It’s this attention to the tradition of chocolate making that has made Ganong unique. But more than that, the company remains an anomaly amongst confectionary businesses in North America because it still exists.

“Ganong’s stayed independent,” says McCallum. “So its role in the Canadian confectionary industry is different than many other confectionary firms. It’s big. It has national and international markets. But it has stayed an independent firm.”

Part Two- Getting Serious about Chocolate

The relationship between the Ganongs and St. Stephen isn’t one sided. With all Ganong has done to support the community, it seems that without the enthusiasm of a small community, a Canadian confectionary of that size could not have sustained itself.

“The factory, in essence, feels like it has always been here,” says Maria Kulcher, chairperson of Chocolate Fest, “The Ganong family simply has been part of the landscape of the community, and the economic landscape of the community.”

In a way, the town’s history is the history of the Ganongs. The stories of the chocolate bar, as well as the triumphs of the family company, are told by residents with the nostalgia of a personal experience. They inform the collective sensibility of the people.

“You have pride being from St. Stephen,” says Mayor Purcell. “There’s a loyalty to Ganong based on the idea that they’re one of ours.”

Chocolate has even infiltrated politics.

John Ferguson, the Chief pat-richardistrative Officer for St. Stephen, says even today chocolate is used for diplomatic reasons.

“We don’t host any diplomat where we don’t have a box of chocolates or chicken bones,” he says.

If the Ganong brothers pulled the town together after the fire, it was Whidden, the third generation president, who solidified the company as St. Stephen’s own.

David Folster, author of The Chocolate Ganongs of St. Stephen, wrote that Whidden “faced a double hex of taxes and internal dissension that almost buried the company.”

Years back, the company sold its failing soap division, only to have the buyer close down and relocate. After that, it became family policy to save the company’s struggling divisions, for Whidden’s fear that if they lost them, the town would too.

“For some years in the thirties, the business wasn’t making money. They were buying supplies, paying salaries, selling their product and just breaking even or running a loss,” says McCullum. “But they were supporting all those people who were working in the business, and maintaining the brand presence so that when things improved they’d still be there.”

But if you ask a St. Stephener about Whidden, you’re more likely to hear that he was always walking his dog, or what it felt like to be greeted by his kind, square face.

McCullum got to know him well while studying the company. On Friday’s he would come greet her before his meetings, leaning back in his chair and watching as she studied the company’s finances on the secretary section of his large wooden desk.

“And he’d say, ‘What have you found so far?’ and I’d have questions for him and he’d have stories for me,” says McCullum. “He was a great storyteller.”

On one of his walks through town, Whidden ran into a local bank manager. The two chatted on the sidewalk outside the factory, overlooking a parking lot, packed tight with the cars of Ganong employees.

“I look at the cars in that parking lot, and those are good cars. Those aren’t junkers,” said the bank manager. “People have got those cars with loans from my bank, and I was willing to give them ‘cause I knew they were working at the factory and could pay them off.”

Part Three- Pockets full of Chicken Bones

(Originally published in the now defunct New Brunswick Beacon)